Model Implementations

Money Axioms

/

Expected Value is NOT Market Value

Expected Value is NOT Market Value

Consider a simple casino game. You flip a fair coin. Each time it lands on heads, your payout doubles: $2, $4, $8, $16, and so on. The game ends the first time you flip tails. At first glance, the game seems fairly innocuous. Like most casino games, it comes with a very small chance of winning a very large amount of money. But something interesting is revealed when analyzing it the way a game mathematician would. For a casino to price a game, they must model it first to understand the expected profits and losses. That begins with a computation of its expected value (EV), which is the sum of all outcomes weighted by their respective probabilities.

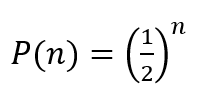

The probability of getting your first tail on the n-th flip is:

The payout in that case is:

The expected value of the game is therefore:

Mathematically, the sum diverges. The expected value is infinite, because the probability of an enormously long streak of heads diminishes at the exact rate that the subsequent payout grows. As such, the average payout grows unbounded.

So now ask yourself the following question. Given that the expected value of this game is infinite, how much would you be willing to pay to play?

If a rational actor priced the game strictly according to expected value, they should be willing to pay any amount of money to play it. But no one would. In practice, it would be rare to find a rational person willing to pay more than a trivial sum. The reason isn’t hidden in the math; it’s in human psychology and practical constraints. No player has infinite wealth, every player has some degree of loss aversion, and the practical utility of potential earnings runs into the law of diminishing returns. The market value of the game is finite because real participants price risk according to their own capital limits and tolerance for volatility, not purely by mathematical expectation.

In other words, the variance between outcomes is also a determiner of market value. This is the reason some people play the lottery. Assuming the lottery tickets are priced appropriately, it is certainly a negative expected value proposition to purchase a ticket. If the odds of winning are 1 in 250,000 and the price of a ticket is $1, then the jackpot will not exceed $250,000. But those that play the lottery do so for the variance; there is a chance, however small, that they could walk away with the jackpot. Those that consider playing the lottery a fool’s errand are unlikely to be persuaded by a larger jackpot, even if that increase in sum caused the expected value of purchasing a ticket to be positive.

It's easy to write off casinos and lotteries as residing in the territory of the irrational. But this disconnect between expected value and market value isn’t unique to flashy games. It extends to everyday financial decisions that most people would consider rational.

Take insurance. By definition, it must have a negative expected value for the buyer. The insurer sells thousands or millions of similar policies, so by the statistics of large numbers, their average payout per policy converges tightly to its expected value. But the insurer has overhead costs (salespeople, underwriters, claims investigators, office space, legal expenses, etc.), and on top of that, in order to stay in business the insurer must return a profit to the shareholders. So the insurer must charge more than that expected payout in order to have a positive expected value. From the buyer’s perspective, that means the expected value is negative, because the transaction is zero sum.

Yet people still line up to buy it. Why? Because when shopping for insurance, rational people are not seeking to maximize their expected value. They are seeking minimize their variance. The insurance premium is the cost of transferring volatility from their personal balance sheet to someone else’s. The market value of that stability exceeds the statistical loss. Rationality here is not about arithmetic; it’s about utility: how people actually experience gains and losses.

We see a similar principle in financial options. The Black-Scholes model provides a theoretical framework to price an option based on its expected value under a set of assumptions. The terms present in the Black-Scholes formula for a European call option are the current stock price, the strike price, the risk-free rate, the time to expiration, and the volatility. In theory, the Black-Scholes model prices the option according to its expected value under a world of continuous trading, no arbitrage, and known volatility. The volatility term represents the realized statistical behavior of the underlying asset, i.e. how much it actually fluctuates.

But in the real market, no one knows the true future volatility. Instead, traders first agree on a price, and from that price we can back out the implied volatility, which is the volatility level that makes the Black-Scholes equation yield the market price. The market value of the option is therefore determined by consensus, emotion, and demand for exposure to or protection from risk.

The difference between implied volatility (what the market expects) and realized volatility (what actually happens) is not necessarily an error. In no way am I claiming that the options are priced incorrectly, any more than I would claim that insurance premiums are priced incorrectly. It reflects the genuine market value of adjusting one’s personal exposure to risk. Just as with insurance, investors willingly pay to reduce volatility, or accept it to seek higher returns.

The Money Axioms strategy is designed to exploit that difference. By systematically identifying and positioning around moments when implied volatility and realized volatility diverge, it captures value in the psychological spread between risk itself and the market’s perception of risk. For that reason, it is not dependent on predicting the next coin flip. It’s dependent on understanding under what circumstances people will or will not pay for the chance to flip the coin.

.png)